You’ve taken lessons. You’ve practiced. Now it’s time for the dreaded recital. You don’t want to do this because you are worried that you’ll make mistakes, and people will snicker. Essentially, crash and burn.

On the other hand, you DO want to do this. You’ve taken lessons. You’ve practiced. You want to display your progress. Deep breath. You may make mistakes but no one will snicker. If they’re smart, they’ll be proud for you that you’ve taken this step, while they’re still in the audience.

I have a friend who recently had his recital. He worked hard, practiced, studied the music. He said it went ok and proceeded to give an in depth analysis of his feelings and progress through the event, step by step. It was all quite interesting. He puts lots of thought into whatever he does. What really stood out to me was when he said he had chosen a piece that was difficult and he was really working on perfecting it up to the last second. He said “…from now on, for the sake of performance, I need to know a piece cold three months before, as opposed to “working on it” three months before.”

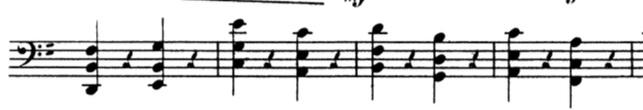

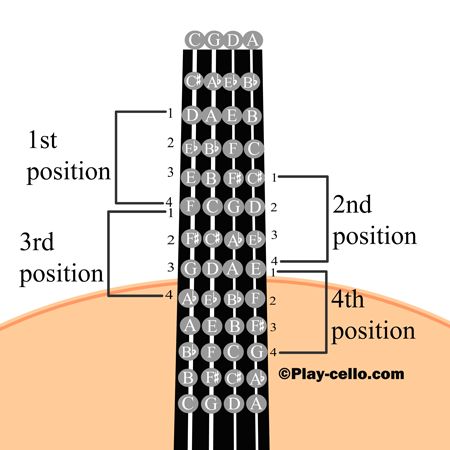

This makes such good sense! The notes typically come first. Learning the spacings, the shifts, and the left hand positions are the starting points. If you have a piece where you’ve already mastered the left hand work, you can really focus on making MUSIC with the right hand and the bow. Learning to taper those last beautiful notes in the phrase. Adding accents where appropriate. Crescendos up the arpeggios and decrescendos down. Really make those pianos quite different from the fortes.

It doesn’t even need to be for a recital. It’s for fun. Take a piece where you know the left hand well and add the real beauty with the right hand. You’ll surprise yourself.